Writing through tears: Building resilience in student court reporters

EDU6149

"The most harrowing two hours I've ever spent in a courtroom"

Josh Halliday, The Guardian

Introduction

In August 2023 journalists covering the trial of Lucy Letby - the British neonatal nurse found guilty of murdering seven newborn babies and attempting to murder six others - sat in a Manchester courtroom and for two hours listened to harrowing statements written by 13 bereaved parents. Their job was to report the full horrors of Letby's crimes, the impact on the families and the jail sentence handed down by the judge. Letby, who worked at the Countess of Chester Hospital, was sentenced to 13 whole life sentences in her absence for her horrendous crimes. Following the hearing Guardian journalist Josh Halliday tweeted about the impact of the case on him.

Traditionally court and crime reporters are a tough lot who don’t show their emotions. But times are changing. Five years ago, based on my observations as a court reporter, it is unlikely journalists would publicly admit feeling upset about a hearing. But following Josh’s tweet, other journalists also admitted being in tears in court.

Dan O’Donoghue, a BBC reporter, replied: “Completely agree with Josh. This morning was one of the hardest I’ve ever had as a journalist, thoughts with all the families,” while Liz Hull, Daily Mail reporter for the north of England tweeted: “Echo this, not ashamed to say I also shed tears as these statements were read, so harrowing to listen to, the bravery of these families is astounding.”

Conventionally reporters ignore their emotions, get on with the job and don’t show emotional distress because it’s a sign of weakness. But journalists are human beings first and reporters second and we should never forget that. In recent years, anecdotal evidence suggests young journalists entering the profession and students on journalism degree courses, are struggling to deal with exposure to raw human emotion and distressing details, particularly of the kind heard in court. So, how do we address this as educators?

A daily beat of death and destruction

Journalists report daily on death and trauma but are expected to do so with professional detachment from their emotions. However, it is unrealistic to expect story tellers not to be affected by the stories they tell and the emotions of the people they interview.

There is overwhelming evidence reporters who witness trauma and disaster are at risk of physical, emotional, and psychological injury (Buchanan & Keats, 2011). And while older studies focused on war reporting and major tragedies, such as the 9/11 terror attacks, recent research has found a rise in journalists reporting on every day events suffering Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS), and vicarious trauma (Seely, 2019). The result being burnout and reporters leaving the industry after short, unfulfilling careers (Hill, Luther and Slocum, 2020).

In the media industry there is growing recognition students and reporters need to undergo resilience training so they are better prepared for the situations they might face in the workplace. As a result of such training implemented by the University of Sheffield, the UK’s National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) updated its performance standards to ensure resilience training is embedded in accredited courses. (NCTJ.com 2023).

Newspaper editors in the UK have also reported reluctance among young reporters to go to court through fear of being emotionally affected. Similarly, interviews with tutors in higher and further education institutions have reported a reluctance among students to engage in the practical teaching of court reporting, and more students finding court reporting assessments difficult to handle emotionally. (Bradley and Heywood, forthcoming 2024).

Following the Covid 19 pandemic I reviewed formal feedback for the JNL230 Court Reporting module as module convenor. Due to the large cohort (over 100 students) learners attend criminal courts in small groups. The module is summatively assessed through a portfolio of court stories and students must attend in order to observe hearings, take notes and apply classroom learning to write ‘news’ stories. Many students reported feeling nervous and scared of going to court and wanted more support before attending by themselves. This made me reconsider learning and teaching activities. I wanted to give students the best possible preparation for court reporting in the real world. I also considered academic literature on experiential learning and role play.

Learning through doing

Kolb’s (1984) model of experiential learning explains students learn through experience. This is applied in various ways in journalism education. Dewey (1958) emphasises the importance of learning through doing and reflection, and suggests a combination of formal teaching and ‘direct learning experiences’. This gives students the opportunity to put into practice what they have learnt in the classroom. Research shows classroom simulations have the potential to better prepare trainee journalists and help them adhere to ethical norms and practices for reporting on trauma and violence. They make course material ‘relevant, stimulating and vivid’, thus sparking student interest (Amend, 2012).

I took a two-pronged approach and designed an immersive experiential teaching event and organised guided visits to Sheffield Crown Court. The aim was to provide a safe and controlled environment for students to understand the graphic nature of the content heard in the courtroom and improve their resilience.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

The Moot Court trial, February 2023, University of Sheffield

The trial

The mock criminal trial was held in February 2023 in the law department Moot Court. The event was compulsory for Level Two students on the BA Journalism Studies programme and MA students on practical journalism programmes - 150 students.

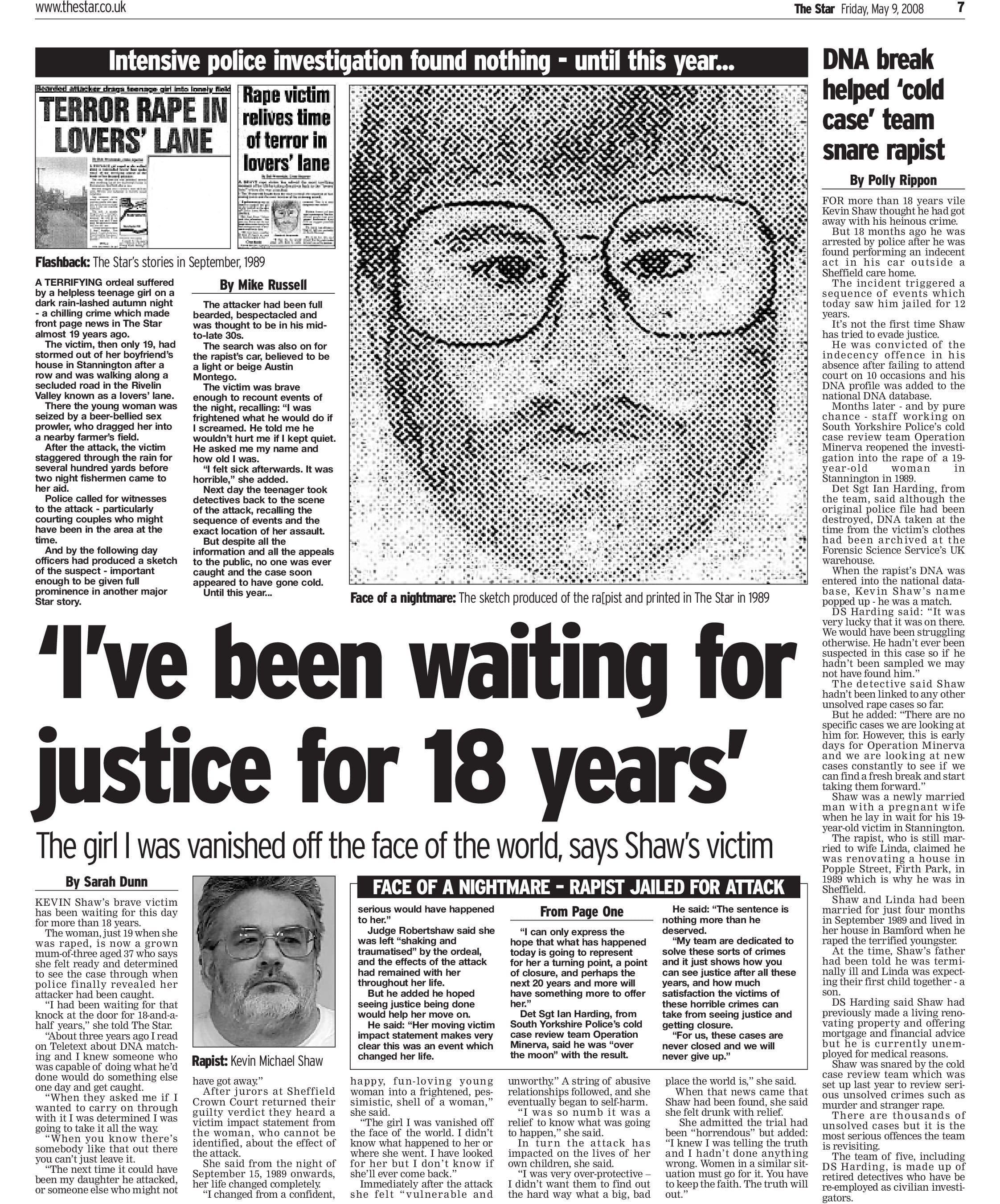

I wrote a 40-minute ‘play’ based on a real rape case I attended in 2008. Professional actors were hired for the main roles, with volunteers from the University Drama Society in minor parts. Content warnings were issued to ensure students received sufficient notice the hearing would contain sensitive and potentially graphic information. This was reiterated on Blackboard, the University’s virtual learning environment. Professionals from the University’s central well-being team provided a supportive session immediately after the mock trial to encourage students to analyse and reflect on their reactions and seek professional support if needed.

Students observed the hearing rather than taking notes and writing a news report as they would in real life. This was to allow them to analyse their emotions in a safe environment, whilst simultaneously experiencing the formalities of the courtroom and applying media law knowledge from semester one. The material was not censored to make the students feel more comfortable. The mock trial enabled students to recognise their own, normal emotional responses, and identify relevant coping strategies. Actors playing the usher, judge, the prosecution and defence barristers wore black gowns, as used in criminal cases in Crown Courts in England and Wales. The judge and prosecution and defence barristers wore wigs as they would in the Crown Court.

The case related to a historic rape allegation, involving a female victim attacked 20 years previously by a man caught due to technological advances in DNA processing. The prosecution case was outlined and the alleged victim was called to give evidence under oath. The actress recalled the sexual attack in graphic detail, becoming increasingly upset and explaining she had been raped. She was cross-examined by the defence barrister and defended herself against allegations she was lying. There were three emotional outbursts from an actress playing the victim’s mother sitting in the audience among the students.

Afterwards students were given a 15-minute break to digest their reactions with peers and tutors. During the well-being session the advisors explained it was normal to have a response to hearing difficult content but some people might need further support. They explained how a response to trauma and vicarious trauma can display itself, including physical and mental health responses. Generic wellbeing advice was given such as rest, eating a healthy diet, mindfulness and exercise.

The Moot Court actors with Lisa Bradley and Polly Rippon from Journalism Studies. Picture: Muhebur Shah

The Moot Court actors with Lisa Bradley and Polly Rippon from Journalism Studies. Picture: Muhebur Shah

Students wrote a 300-word reflection which was not assessed but used to gain informal feedback and suggestions for improvement. The mock court case was widely praised by staff, students and industry professionals and won the University of Sheffield Vice Chancellor's award for Teaching Practice 2023.

Organised visits to court

I also organised visits to Sheffield Crown Court. These included a tour of a courtroom and a question and answer session with a court clerk and a senior judge. The aim was to put students at ease and ensure they were comfortable with logistics - for example navigating security arches, having bags searched, finding courtrooms and interacting with staff. Students were given the opportunity to question the judge.

Focus groups

Nine weeks later two focus groups were held for BA and MA students to gauge their views on the preparation received for attending court. This gave them the opportunity to attend real criminal court hearings. The first consisted of six undergraduates (five female students and one male). The second contained four post graduate students and one BA student (one male and four female). Tutors led structured interviews asking set questions. None of the participants had been to court before.

Analysis shows all students found the mock trial a positive experience but some were surprised by the level of graphic detail.

One MA student said: “It was uncomfortable to listen to, but I think it needed to be.”

Some students separated their professional responsibilities from their emotions. One said: “You've got that notepad as a little barrier, but then when someone is in tears on the stand, while someone is ripping apart their character, it's very hard to stay neutral and not have an emotional reaction to that.”

An MA student added: “If it hadn't been really graphic then it would obviously have been unrepresentative of what we're actually going to hear. So I think, in a way, it was actually quite good that it was so extreme.”

Wigs and gowns

The mock trial helped students understand court procedures. One BA student said seeing the courtroom layout, and the wigs and gowns worn by the actors put her at ease. A BA student said the mock trial gave him the confidence he knew what to do when he went to court.

Taking part in a shared experience with peers was valuable for one BA student.

A BA student said sitting through such a ‘harrowing’ case had equipped her for other upsetting cases she might encounter.

Usefulness

All participants agreed the mock trial was useful. One student was relieved to have something to ‘soften’ the ‘intimidating experience of stepping into a courtroom for the first time’. Another said it enabled her to put her court reporting skills into practice before the “real thing,” when it was “too important to mess up”. She said without the mock trial experience, she would have needed more “hand-holding” adding: “I'm ‘court qualified' now.”

“I felt fine the first time I went with one friend. I think if we hadn't had that (mock case) I would have really struggled to motivate myself to just go to court. I would have had way too many things that I'd be stressing about.”

Another learner said it made her realise how important it was for journalists to cover emotionally difficult cases.

Guided court visits

The Crown court visits put students at ease when attending on their own.

Another MA student added: “Court is intimidating anyway, I think the visit, going before with a lecturer and having the whole group there and having a specific talk was really nice.”

A third student explained hearing from a judge had made her seem ‘more human’. She said: “The judge talked about her personal experiences, and it made it less scary.”

Another MA student explained she would have liked advice on handling abuse from members of the public.

While the students in the focus groups collectively agreed on the importance of attending the mock trial and court visit, all said the well-being session was too general and needed to be specifically-targeted at journalism students.

What do the professionals say?

I also surveyed five journalists in the UK aged between 39 and 54 with 125 years’ journalism experience between them. I wanted to find out what resilience training they’d received and whether or not they felt it was important. One participant was female, four were male and all were trained by the NCTJ (National Council for the Training of Journalists). Four were specialist court reporters and one a general news reporter who had covered more than 2,000 criminal court cases during his 27-year career. One was freelance while others wrote for regional press titles and national news agency The Press Association. They completed an 18-question survey. Analysis of their responses shows there is much work to be done to prepare newly-qualified journalists for the realities of covering the criminal courts.

No resilience training in the past

None of the participants received any support or training at university, college or in the newsroom to deal with graphic content, attend court or speak to traumatised interviewees. All passed preliminary exams in media law prior to starting their first journalism jobs but there was no practical preparation for going to court. One journalist said: “I was taken to a magistrates court once, to see what it was like. But there was little in the way of training or preparation.”

The respondents said there was no support or training for covering court and most relied on colleagues or more experienced reporters to show them the ropes.

The journalist said he had supportive editors but didn’t speak up for fear of being perceived as 'weak' and taken off court reporting, which he loved.

For one specialist, it was only when he suffered insomnia after years of court reporting that his bosses took action and he was given general news duties to ease over-exposure to court.

Another reporter remembered being informally mentored by two experienced Crown court reporters who worked on rival newspapers: “They really showed me the ropes and I learnt more from them than perhaps any other source,” he said.

Drinking and bantering

The reporters used a variety of coping mechanisms including drinking alcohol, talking to friends and family, compartmentalising, bantering with colleagues and exercising.

While some were unaffected by what they’d heard, others found they became more affected the longer they worked as court reporters.

The professional journalists all agreed formal trauma and resilience training should be an essential component of journalism training, whether delivered on courses or in newsrooms. They said trainee reporters should be able to speak up and seek help at work without fear of looking weak and reporters should be warned about the possibility of being physically or verbally threatened by members of the public at court.

Conclusions

After reflecting on student feedback from reflections, focus groups and the responses of the professional journalists surveyed, I will implement improvements to LTAs and the mock court case next year. Students will take notes during the case, so the notebook acts as a 'barrier' enabling them to disengage from the content. The well-being session will be held separately, allowing for group discussion and focus specifically on the mental health challenges experienced by journalists in the workplace, rather than offering generic well-being advice. I will ensure appropriate coping strategies are proposed and draw attention to the less healthy examples of the past - for example excess alcohol consumption as highlighted by professional reporters.

The experiences of the professionals show a cultural change is needed on journalism courses and within the media industry in general around mental well-being. There is also growing awareness that significant well-being issues have arisen among the student population in higher education. This is recognised in the Universities UK Step Change: Mentally Healthy Universities Framework which advocates a “whole university” approach to wellbeing (Universities UK 2021). Research conducted in law schools has found poor mental health exists throughout the legal profession (McKeown, 2023) and well-being should be embedded in programmes rather than left to university well-being teams. He states: “Well-being should be a core component and pervasive throughout the law school curriculum, to provide students with the tools and mechanisms to have a healthy and balanced student life that can form the basis of a healthy and balanced career.”

As a department, we have embedded resilience training in all our programmes and will continue to develop this strand of teaching. This academic year all students on our programmes will receive six hours of resilience teaching instead of one lecture. Topics such as domestic and sexual abuse, reporting on suicide, coping with online abuse and interviewing the bereaved and victims of abuse are covered. This training has been brought forward on MA programmes to ensure well-being is embedded from day one. This is not without its challenges, however. These include timetabling - our students have a packed teaching timetable already, staff availability, room availability, willingness of staff to address well-being issues without professional training, and financial constraints.

In relation to court reporting and media law modules I will continue to adapt learning and teaching activities to ensure student well-being is at the heart of delivery. This will include resilience lectures, guided tours of court, a mock court case, analysis of court transcripts, discussions around broadcasted sentencing remarks, and the use of role play or AI-generated scenarios in workshops. However, there are likely to be other methods in use already and this is an area in need of further research. There should also be sharing of best practice in preparing students and young journalists for court reporting, globally.

References

Amend, E., Kay, L., and Reilly R.C., 2012. Journalism on the Spot: Ethical Dilemmas When Covering Trauma and the Implications for Journalism Education, Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 27:4, 235-247, DOI: 10.1080/08900523.2012.746113

Bradley, L., and Heywood, E., forthcoming, 2024. Journalism as the fourth emergency service: Building trauma and resilience training into journalism education. Peter Lang.

Buchanan, M. and Keats, P., 2011. Coping with traumatic stress in journalism: A critical ethnographic study. International journal of psychology, 46(2), pp.127-135.

Dewey, J., 1958. Experience and nature (Vol. 471). Courier Corporation.

Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential Learning. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Hill, D., Luther, C.A. and Slocum, P., 2020. Preparing future journalists for trauma on the job. Journalism & mass communication educator, 75(1), pp.64-68.

McKeown, P., 2023. A Broken Profession Both Mentally and Physically: Is Wellbeing the Foundation to a Healthy and Resilient Future?. In Wellbeing and Transitions in Law: Legal Education and the Legal Profession (pp. 63-86). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

NCTJ.com https://www.nctj.com/news/resilience-training-to-be-delivered-to-students-on-all-nctj-accredited-courses/

Seely, N., 2019. Journalists and mental health: The psychological toll of covering everyday trauma. Newspaper Research Journal, 40(2), pp.239-259.

Universities UK, Step Change: Mentally Healthy Universities (Universities UK 2021) <www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2021-07/uuk-stepchange-mhu.pdf#page=12> accessed October 19 2023.